I. Introduction

The intention of this short macroeconomic analysis is to discover whether the T-bonds trading will become a major factor in investment decisions of individual and institutional investors in the near future. The aim is to shed some light on such a trend coming from the global capital markets that might shape a new investment environment.

For the last three decades before the 2007 crisis, the global economy has experienced a progressive reduction in real interest rates as a result of a significant decline in investment returns in advanced economies1. This process was supported by world savings exceeding world investments. However, recently we observe an increasing physical investment demand in emerging markets that is anticipated to put upward pressure on real long-term rates2. Higher rates would enable investors to earn better returns from fixed-income securities and possibly rebalance markets and maturities.

If, as anticipated, real long-term rates increased, such as the real yield on a 10-year Treasury bond, the shift away from fixed-income instruments towards equities and alternative investments or pure liquidity could be reversed. These expectations predetermined the interest in looking at the investment decisions, particularly of institutional investors, to find out whether there is a shift towards T-bond holdings.

II. The approach in this case study

Investment analysis has already demonstrated differences in how people in different countries actually allocate their wealth3. In a world of Arrow-Debreu complete-markets4, the nationality of firms has no bearing on optimal investment decisions, and the international security prices determine a country’s equilibrium investment level. However, real world asset trade does not usually consist of complete-market securities; on the contrary, it exchanges a set of national economies’ equity shares and risky bonds.

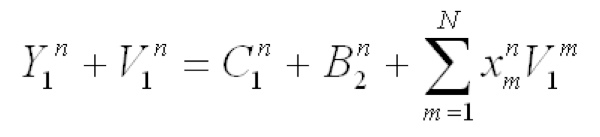

A resident of any country n usually divides their income Y between consumption C and saving S, as the country n’s saving takes the form of net bond purchases B and net purchases of shares x in country m’s future output V:

All residents are bound by such constraint in making their investment decisions.

In order to determine whether there are signs of a reversal in the pattern of investment decisions, the analysis focuses on the stock and bond markets of two contrasting countries – the USA’s NYSE and NASDAQ OMX, and China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen markets. It is apparent that not only their patterns of investments and saving rates differ markedly, but they are also to a considerable extent complementary.

III. Equity and Bond Markets

A. China’s emerging markets

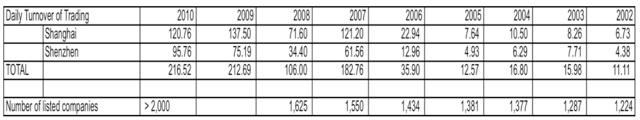

China’s capital markets have been expanding significantly for the last decade. In the first quarter of 2011, the two stock bourses combined ($4.2 trillion) surpassed the Tokyo Stock Exchange of $3.6 trillion5. The total trading was affected by the financial crisis in 2008, but it appeared to recover in 2009 and 2010 (Table 1). The trading volume of national stocks represents China’s A-shares, which consists of CNY-denominated shares listed on Shanghai and Shenzhen and B-shares (listed on Shanghai and Shenzhen with trading in foreign currencies). H-shares are not included since they are only listed on Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Table 1: Stock trading on nationwide basis (Million Yuan)

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2009; People’s Bank of China Statistics

Most domestic market participants are individual Chinese investors. The institutional investors play a relatively limited role and their investment in stock markets is restricted. Investment regulations put ceilings on the proportion of assets institutional investors can allocate to stock. International investors can only make investments within their limited QFII6 quotas. As may be seen from Table 2 long-term institutional investors’ participation is limited, and domestic family offices, foundations and endowments are absent from the stock market.

Table 2: Market share of investors in China’s stock market (Dec 31st, 2007)

| Type of Investor | Market share |

| Individual investors | 51.30% |

| Mutual funds | 25.70% |

| Ordinary investment institutions | 16.60% |

| Insurance companies | 2.50% |

| QFII | 1.70% |

| Securities firms | 1.40% |

| National Social Security Fund of China | 0.80% |

| Pension funds | 0.01% |

Source: China Securities Regulatory Commission

At the beginning of 2011, retail investors continue to account for an increasing portion of the market (60%) as Chinese households shift their savings into stocks and mutual funds. Additionally, the number of investment funds has increased, with many managers partly owned by international companies. QFII holdings still only account for less than 2% of total stock market holdings, but their influence is much more recognized due to the depth of their fundamental research and better risk management. However, the role of foreign investors on the China’s stock exchanges is very limited. Also the home bias portfolios of individual investors are evidently present as a result of restrictions on holding foreign stocks.

The government plays an active role on the stock markets of China as the largest investor in state-owned enterprises. The State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council is the majority investor in China’s state businesses and acts on behalf of the government. China’s regulatory bodies have a major role in changing the composition of the investor base. The China Securities Regulatory Commission has indicated that it may expand the supervision of fund managers and include on-site investigation of fund managers. Further regulations will be developed, which undoubtedly will improve the competition between investors7.

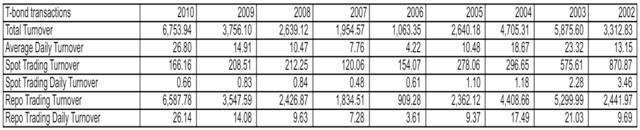

The other important market for resource allocation of national saving is the bond market. In 2010, RMB 9.51 trillion of bonds were issued, 80% of them government bonds, central bank notes and policy bank debentures8. Corporate bonds are small but fast-growing segment of the debt securities market. In this respect, our focus is on the T-bond trading on the exchange (1%) and interbank markets (94%), as these are the two major bond markets (Table 3 and Table 4)9.

Table 3: Treasury Bonds trading on stock exchanges (Shanghai and Shenzhen)

Million Yuan

Table 4: Treasury Bonds repurchase trading of national interbank market (millions)

Source: People’s Bank of China Statistics

More than 60% of the bonds issued by the central government have a maturity above 5 years10. The China bond market is not highly diversified, products are limited to low profitability, long-term, low risk T-bonds. The Central bank notes are usually shorter (1-3 years) as the yield is determined. A yield curve for the interbank market has been established and provides a basis for the pricing of products.

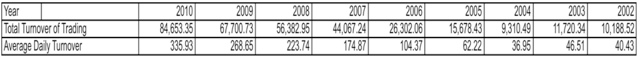

In order to discover whether the Chinese investments are stocks prevailed or not, Table 5 gives the share of China T-bonds turnover in stocks trading turnover. There has been an observable trend of a shift towards equities on the Chinese two bourses since 2005, where the individual Chinese investors are the dominant players.

The focus is on growth stocks, which represent the majority of the investment stance, and provide satisfactory short term profits. This trend, given the high internal demand, has not changed over the period of the financial crisis. In contrast, on the national interbank market where the institutional investors dominate, the trend is towards the T-bonds – low risk, long-term investments. This is partially explained by the strict regulations for financial institutions which channel Chinese savings into medium to long-term investments. That is, in China the shift towards T-bonds trading has been driven by domestic institutional investors.

Table 5: Share of China T-bonds turnover in stocks turnover

| T-bonds turnover on Stock Exchanges/Stocks turnover | T-bonds turnover on National Interbank Market/Stocks turnover | |

| 2002 | 118.36% | 364.00% |

| 2003 | 145.95% | 291.13% |

| 2004 | 111.15% | 219.93% |

| 2005 | 83.38% | 495.14% |

| 2006 | 11.75% | 290.73% |

| 2007 | 4.24% | 95.68% |

| 2008 | 9.88% | 211.08% |

| 2009 | 7.02% | 126.31% |

| 2010 | 12.38% | 155.15% |

Source: Author

B. USA’s developed markets

The simplification of analysis on Chinese emerging markets was dictated by a shortage of detailed data and a lack of highly diversified products on both equity and bond markets. Moreover, the limited role of institutional investors on the stock market allowed an examination of the equity turnover without controlling for the composition of investor base. Studies have demonstrated that trading by institutions has a more pronounced effect on volume autocorrelation than trading by individual investors11.

However, to explore the equity and bond developed markets of the US, a more precise analysis is required. A relatively large amount of research has already been done12. Studies identified information and trading costs as significant factors that affect how frequently investors alter their expectations regarding the firm and adjust their holdings in response to changed expectations.

In fact, different institutions pursue different investment strategies. A study by Armstrong and Gardner finds that greater equity holdings by depository institutions, private pensions, closed-end-funds and brokers and dealers increase NYSE turnover, while greater holdings by bank-managed trusts and estates, insurers other than life insurers, open-end mutual funds, state and local governments and their pension funds reduce it13. They also found that financial institutions pursue different strategies with different types of stocks, thus NYSE turnover differs from NASDAQ turnover (Table 6).

Table 6: Share turnover

| Share turnover14 | NYSE | Holding period | NASDAQ | Holding period |

| 1985 | 54% | 22 months | 72% | 13 months |

| 1995 | 60% | 20 months | 180% | 6 months |

| 2002 | 104% | 11,5 months | 280% | 4 months |

A more recent study conducted by the IRRC Institute in 2010 demonstrates differences in fund managers’ national and global strategies. Their sample consists of long-only equity managers that pursue domestic and international strategies15. The study finds that managers of UK, Canadian and Australian equity strategies funds had the lowest average turnover value while European, international and US strategies had the highest average turnover levels. Table 7 illustrates how managers with international strategies appear to have a higher propensity to react to market changes.

Table 7: Turnover variation by region

|

Min |

Average |

Max |

||

|

Australia |

5.20% |

15.7% |

65.4% |

142.7% |

|

Canada |

8.90% |

12.4% |

55.5% |

194.6% |

|

Europe ex UK |

25.00% |

12.2% |

78.3% |

154.3% |

|

Europe incl UK |

40.50% |

18.3% |

90.5% |

253.9% |

|

Euro zone |

16.70% |

35.1% |

72.6% |

115.3% |

|

International |

27.30% |

12.2% |

78.6% |

193.7% |

|

UK |

8.20% |

24.2% |

54.6% |

165.9% |

|

US |

23.90% |

14.5% |

76.9% |

232.8% |

Source: IRRC Institute Study (2010)

Both mentioned studies provide evidence in terms of stock prevailing investment decisions where institutional investors pursue a variety of strategies with different types of stocks in order to optimise their portfolios’ returns. This has been an observable trend for a long time and proves the existence of significant shortening in the holding period of investments.

Nonetheless if we look at the estimated ownership of US Treasury securities, there is an emerging upward trend in the privately held T-securities (Table 8). The high participation of foreign and international investors – 31% in 2011 comparatively higher than the 20% ownership in 2000 – contributes to this trend. Perhaps there is a parallel shift towards fixed-income securities on the horizon that will further develop in the medium to long-term future as the foreign investors17 play a major role.

Table 8: Estimated ownership of US Treasury securities

|

Federal Reserve and intra-governmental holdings |

Total privately held |

|

|

March 2002 |

52.56% |

47.44% |

|

March 2003 |

52.48% |

47.52% |

|

March 2004 |

50.88% |

49.12% |

|

March 2005 |

50.42% |

49.58% |

|

March 2006 |

50.85% |

49.15% |

|

March 2007 |

51.71% |

48.29% |

|

March 2008 |

49.74% |

50.26% |

|

March 2009 |

43.01% |

56.99% |

|

March 2010 |

41.12% |

58.88% |

|

March 2011 |

41.76% |

58.24% |

Source: US Treasury, Statement of the Public debt of the US; Federal Reserve Bulletin

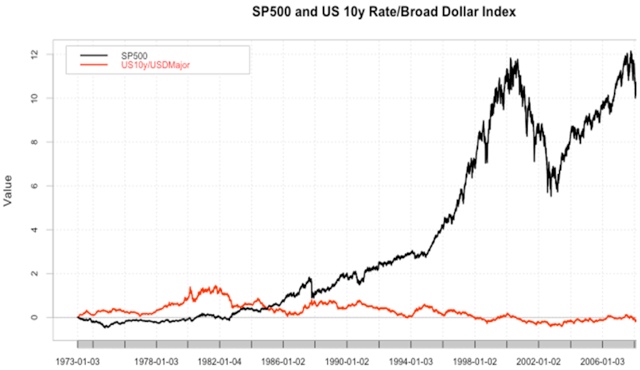

Furthermore, comparing the performances of SP500 Index and 10y-T bond Rates/Broad Index (chart 1) for the period of 1973 until 2007, the attraction of equities was clearly defined and the returns were much higher. From 1985 the returns from fixed-income instruments were at historically low levels, which reflected the low real long-term rates.

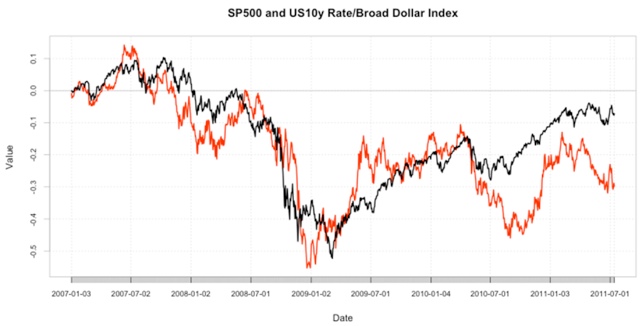

Chart 2 demonstrates very early signs of a reversal in the existed trend before 2007, where now the equities and the T-bonds performances follow a similar path. It is evident that the attraction of the T-bonds has increased and this new direction is likely to continue in the future as the higher long-term rates are anticipated.

Chart 1: Cumulative returns from stocks and 10y-T Rates/Broad Index18, 1973 – 2007

Data source: www.federalreserve.gov, R-plot

One thing the financial crisis proved is that sovereigns are equally vulnerable to default as corporations, and thus, the T-bonds are no longer risk-free assets. Not only this, but also there is high interdependence between equities, US bonds and US currency, which appears to be an emerging pattern in the US investment environment (chart 2). Moreover, the privately held US Treasury securities have gone up significantly mainly due to foreign investors’ purchases and adds a novel driving force to this potential shift towards fixed-income instruments.

Chart 2: Cumulative returns from stocks and 10y –T rates/Broad Index, 2007 – 2011

Data source: www.federalreserve.gov, R-plot

IV. Conclusions

This short analysis aimed to explore any observable change in the investment decisions as a consequence of the increasing physical investment demand in emerging markets. I suggested that the movements towards T-securities are early signs of a shift towards medium to long-term fixed-income products in anticipation of higher real long-term rates. While it may be too early to conclude that this trend might turn out to be a structural shift, there are certainly signs from the Chinese and US markets that this may be the case.

Viara Bojkova is Senior Analyst at the Global Policy Institute: http://www.gpilondon.com

July 2011