The economic situation in Europe is deteriorating day after day and now it is the turn of the ECB to make things worse with its irresponsible monetary policy. Although the economy in China is, apparently, much heathier than the one in Europe, China needs to be careful not to fall into the same trap and avoid the temptation to play with interest rates too much. Lowering benchmark interest rates, as central bank do traditionally is already a dangerous practice. But, adopting unconventional monetary tools, like QE, and playing with long-term rates is even worse and will create un-intended consequences that will put Europe on its knees, for a very very long time.

The ECB has launched in QE program that consists of purchasing about 60bn Euros a month of a mix of government (50bn) and other bonds (10bn), and will do so for the next 18 months, until September 2016. The bonds that are target of the QE plan have maturities ranging from two years to thirty years. Basically, the ECB is acting, for the first time, on the whole range of the yield curve. During their normal course of operations, when central banks change benchmark or prime rates, they mostly affect short term yields, while long term yields remain, more or less, unchanged. Therefore, when a central bank lowers its base interest rates, then short-term rates tend to fall more than long-term rates, resulting in a steepening of the yield curve. The goal of this intervention is to facilitate short-term borrowing in order to solve any short-term credit crisis and allow corporation to get on with their business. Long term rates are not affected. Therefore, this kind of intervention does what a central bank is supposed to do: give a hand in the short –term, but without altering the long term credit equilibrium, over which it has little control.

This time it is different and more dangerous. The ECB QE plan is directly targeting bonds with all maturities; in particular, it will target bond with long maturities, up to 30 Years. The effects of this kind of intervention are going to be much more difficult to predict, let alone control them. This is extremely worrying.

The purchase of long-term bonds via QE will produce almost the opposite effect on the yield curve. This time around, short term rates do not move too much, while yields on long maturity bonds decrease substantially. The net effect is a flattening, not steepening, of the yield curve. As the curve becomes flatter and flatter every day, there will be a point where it start to be inverted, meaning that long-term rates will be lower than short term rates. Even if this inversion of the curve were not to happen, we would still experience a more flat yield curve, with interest rates on short-term German government bonds being pretty much the same as rates for long-term bonds. Corporate credit rates would tend to move in a similar fashion, because the maturity spread would, pretty much, remain unchanged. In other words, corporate credit rate curve will also flatten. Therefore, a corporation that wishes to borrow money in the debt market would end up paying similar interest rates, no matter if it borrows for 2 or 30 years. An unusual phenomenon.

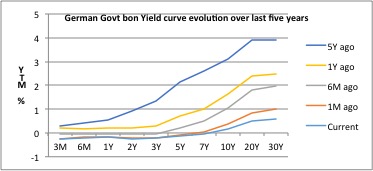

The speed at which this phenomenon is happening is evident from the chart below that shows the evolution of the German Bund yield curve over the last five years.

Back in 2010 a 30-year bond would offer a return of almost 4%; today it offers an incredibly low 0.5%. Only a week ago, the same 30-year bond would have yielded 1%. What this means is that in five days only, the longest maturity bond yield has halved, from 1% to 0.5%. Pretty dramatic. Even more unusual is that almost all German government bonds with maturity of less than 10 years offer negative yields: in other words, investors today are happy to buy bonds at more than 100, receive no coupons at all, and receive 100 after, say, 8 years. Germany has, therefore, become the vault of Europe, and charges investors a fee for keeping their money.

The logic of lowering interest rates to stimulate economic growth is that by offering cheaper credit to corporations, they would invest more than if interest rates were higher. Those investments should create job opportunities, increase production and, ultimately, GDP growth. This logic is correct on the assumption that Europe were full of entrepreneurs with brilliant investment ideas, whose growth opportunities are impaired by the high cost of money. Under this hypothetical scenario, lowering the interest rates would unlock this creativity potential and those entrepreneurs would indeed contribute to the economic growth of the region. To put it emphatically, in order QE to be effective, there should be a long line of entrepreneurs and corporations full of good investment ideas, all queuing outside the banks, waiting for money to become cheaper. The problem is that this is not the case, nor in Europe neither in China. Therefore, a policy of lowering rates can cause un-intended effect, such a mis-allocation of capital.

Since the effect of QE is to make long-term rates comparable with short-term rates, this policy will not only encourage corporates to borrow money that they will not necessarily make good use of, but, extremely worryingly, it will also tempt those corporations to take long term loans. Very And it is exactly this temptation that will create massive mis-allocation of capital for a long period of time and make the current European economic crisis last for longer and likely destroy any little hope left of economic recovery.