General Introduction

Health care spending in China is increasing rapidly. According to a Deloitte report released in 2015, the country’s annual expenditure is projected to grow at an average rate of 11.8 percent a year in 2014-2018, reaching $892 billion by 2018. Spending will be driven primarily by consumers’ rapidly increasing incomes and the government’s public health care reforms.

Despite these positive numbers, China’s health care spending, at an estimated 5.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2013, is still much lower as compared to OECD countries. The country also has a large health care demand gap due to an aging population, growing urbanization, proliferating lifestyle diseases, rapidly increasing consumer wealth, and the advancement of universal health care insurance. While all of these elements are driving overall health care market expansion, continued development cannot proceed without heavy investment by and strong support from the Chinese government.

China is a vast country with uneven economic development. Rural and urban residents are categorized separately according to the household registration system (hukou), and the government financing systems is different for the two categories of citizens.

After the economic reforms started in 1978 China experienced rapid economic growth in the past two decades, benefiting many sectors of the economy. However, the economic success was not mirrored in the healthcare system. The transition from a centrally planned economy to a market‐oriented economy has caused problems in the public health arena.

There have been several debates regarding China’s healthcare reforms in recent years. Critics, composed primarily of individuals from outside the Ministry of Health, have labeled the past reforms as failures, attributing it to the excessive dependence upon market mechanisms in the healthcare sector. Yet supporters, composed of individuals from within the Ministry of Health, have asserted that past reforms were relatively successful, pointing to the fact that the problems associated with the shortage of health services and drugs during the period of the planned economy have largely been resolved.

In response to the emerging problems in its healthcare system, China has made numerous attempts to rebuild universal coverage system since the late 1990s. The health insurance system collapsed in the late 1970s, and a great number of residents left uninsured. Through decades of effort, the Chinese government has developed three systems, in both urban and rural areas, which provide coverage for more than 90% of the population. The condition was especially troublesome in rural areas, revealing sharp rural‐urban disparities in health insurance coverage and related healthcare services and costs.

Starting from the late 1990s, the government established three new health insurance systems. During the launch of each new health insurance scheme, the government also proposed other measures to provide more healthcare resources to the targeted population. In 2009, the government started a new round of healthcare reform. In the new round of reform, the major goal was to provide universal coverage to all residents, and to target on disadvantage population to improve the healthcare service for them and reduce disparities.

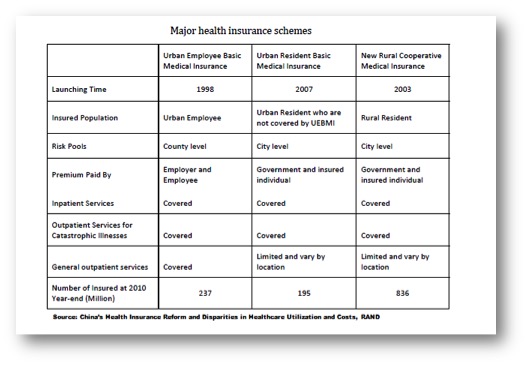

According to a statement by the State Council, the goal of universal coverage is to provide safe, effective, convenient, and affordable basic medical services to all urban and rural residents. One of the most important components of universal coverage is health insurance. Before this goal of universal coverage was officially introduced in 2009 with the Chinese government’s announcement of the blueprint for health system reform, health insurance reforms in both urban and rural areas had resulted in greater health insurance coverage. Three major health insurance schemes were established. The Urban Employees Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) was launched in urban areas in 1998, and the Urban Residents Basic Medical Insurance was launched in 2007. In rural areas, the New Rural Cooperative Medical Insurance (NRCM) was established in 2003. Below follows a brief introduction to each scheme.

- The Basic Medical Insurance for Urban Employees

In 1998 was set the Urban Employees’ Basic Medical Insurance System. This was the first step in re‐establishing the health insurance system in urban areas. The Urban Employees Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) is compulsory based on employment. It provides basic medical insurance coverage for urban employees in both the public and private sectors. Local governments, mainly at the municipal level, set the level of deductibles, copayments, and reimbursement caps according to local economic levels. The UEBMI is financed by premiums from both employers and employees. In their decision, the State Council suggested that the employers’ contribution be 6% of the employee’s salary and the employees’ percentage be 2%. The revenue collected from premiums is distributed evenly into two independent accounts: the medical Savings Account (MSA) and the Social Pooling Account (SPA). All employees’ contributions and

about 30% of employers’ contributions go into the MSA, and the remainder of the employers’ contributions goes to SPA. The two accounts are managed separately and pay for different services: the MSA covers outpatient and emergency services and drug expenses, and the SPA covers inpatient services.

- The Basic Medical Insurance for Urban Residents

In 2007, the State Council issued guidelines to launch the Urban Residents Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI). According to the guidelines, the URBMI covers primary and secondary school students who are not covered by the UEBMI (including students in professional senior high schools, vocational middle schools, and technical schools), young children, and other unemployed urban residents on a voluntary basis.

The main purpose of the guidelines is to provide coverage for urban residents without formal employment with the intention of eliminating impoverishment resulting from chronic or fatal diseases, which can lead to catastrophic medical expenditures. The URBMI was piloted in 79 cities. In 2010, this insurance scheme was expanded nationwide and gradually extended to all unemployed urban residents. The financing of this insurance program mainly comes from participants’ premiums. The government also provides a smaller amount of subsidies, compared to the premium contributions. The premium of the policy is determined by the local government, according to the local economic level, the medical care expense level, and the participants’ household income level. There are extra government subsidies for low‐income

families, disabled students, and young children.

- The New Rural Cooperative Medical Insurance

In recent years, especially since the SARS outbreak in 2003, healthcare reform, primarily in the rural regions of China, has received unprecedented attention from the central government. While a rural health insurance system had existed in China prior to its economic reforms, it floundered during the early 1980s primarily because of the collapse of the rural collective economy. As a result, some 90% of the rural population was left without any type of health insurance coverage. In 2003, the State Council issued the decision to further enhance the rural health care system, aimed at re-establishing the new rural cooperative medical insurance (NRCM). The NRCM scheme covered the rural residents on a voluntary basis in order to avoid impoverishment caused by catastrophic expenses from infectious and endemic diseases.

The NRCM was piloted in 2003 in selected counties. In 2010, the NRCM covered more than 90% of all rural residents. The NRCM was funded by premiums from both the insured and by subsidies from the local and central governments. This was the first time that Beijing had allocated funds from the central government budget to support a rural health insurance plan. The NRCM provides partial coverage for all kinds of medical expenses, excluding some outpatient expenses and drug expenses. The reimbursement caps vary by local economic development levels. The initiation and expansion of the NRCM diminished the disparities in health insurance coverage; however, it is still unknown whether the expansion helped reduce disparities in other healthcare areas, such as healthcare utilization and cost.

A brief overview of the three main insurance schemes is provided in the table below, taken from RAND’s report on “China’s Health Insurance Reform and Disparities in Healthcare Utilization and Costs”

Instead of only providing health insurance coverage, the healthcare reform was a comprehensive system with other measures and actions. These measures and actions worked together with health insurance expansion, providing residents with more healthcare resources.

The12th Five-Year Plan: Consequences on the healthcare system

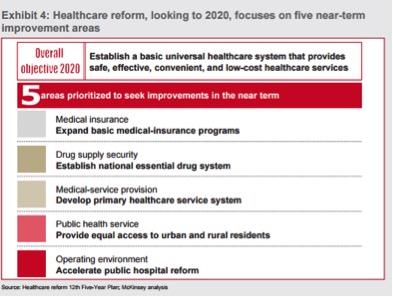

Starting from 2009, the government’s 12th Five-Year Plan (FYP) has set several objectives for the national healthcare system. The image below provided by the McKinsey’ s report on healthcare in China displays the five areas to seek improvements in the near term. The 13th Five-Plan that will be released in 2016 is expected to deepen the healthcare reform, following and strengthening the major issues pointed out in the government’s 12th Five-Year Plan.

As a first order priority, China has to expand further its basic medical-insurance programs. For this purpose

together with the reform of public insurance schemes, Chinese officials have encouraged the development of private health insurance as a supplement to the public scheme. In fact, some local governments have formed partnerships with private companies to manage their public insurance plans.

To encourage the use of private health insurance, the government has announced a pilot plan to give tax breaks to private health insurance policy holders.

The second priority is to establish basic drug supply system. In order to ensure the supply of affordable basic drugs, the central government established a list of essential drugs, and guaranteed the supply of the listed drugs to all levels of medical facilities. Moreover, the health insurance programs provided more coverage for these basic drugs.

A relevant issue in China nowadays is that new therapies are not promptly allowed into the Chinese market because China’s FDA (Food and Drug Administration) has standards inconsistent with those of other countries. This hurts Chinese patients and obviously burns precious time that newly patented medicines have to access the China market.

The third area of the list consists in strengthening the primary healthcare service system in order to provide a wider medical service provision at a general level.

Going ahead in the list, another major objective is to provide equivalent public healthcare service to both rural and urban residents, developing a primary care infrastructure that includes development of community health centers (CHCs) and community health stations (CHSs), combined with a three-tier rural medical network comprising county hospitals, township health centers (THCs) and village clinics.

Aiming to improve the quality of public healthcare in rural areas, medical graduates and retired medical professionals from urban areas were encouraged to go back to work in rural areas.

Training for medical professionals should be further improved at local levels. Healthcare workers were encouraged to attend formal education programs and obtain official licenses. The training of general practitioners for rural areas was included in the Ministry of Education 2010 work plan.

Finally, pilot programs for public hospital reform were started by the central government after 2009.

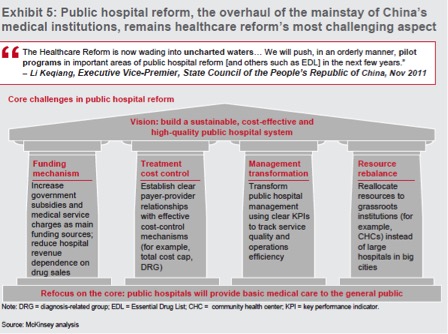

Public Hospital Reform

A new reform took place in May 2014. The State Council released guidelines and a timetable to reform public hospitals. Among the toughest problems the in China’s healthcare economy, is the ongoing difficulties the country’s public hospitals have paying their bills, and how inadequate doctor compensation remains. The roots of every corruption within China’s hospitals have these problems at their core: China’s public hospitals are sorely under-funded, and its doctors under-paid. Longer-term reform requires doctors who do not have to seek out supplementary gray income from pharmaceutical companies, families and hospital management.

Today, publicly-funded hospitals that join the reform are required to sell medicines at the price they bought them, so they won’t be able to overcharge patients and doctors will be much less likely to prescribe excessive medicines. On the other hand, the publicly-funded hospitals are allowed to readjust the price charged on their medical services, such as doctor consultation, so that the hospitals and their medical staff will be decently paid for their work instead of relying on selling medicines. According to Roland Berger’s analysis, the “separation of drug sales from hospitals” and cancellation of “subsidization of medical services with drug sales” policies will be substantially and widely implemented during the 13th Five Year Plan, creating a major, long-term impact on the pharmaceuticals market and industry.

Moreover, the State Council has decided that the authorities should allow the market to determine the price of most medicines, and should turn to negotiations to bring down the price of certain medicines, such as proprietary medicines.

Nowadays, the largest hospitals in big cities (about 1,350 institutions in all) tend to have the highest quality physicians and equipment, and capture the lion’s share of patient flows. By contrast, grassroots facilities such as urban community health centers (CHCs) and county hospitals tend to be underdeveloped, poorly funded, and disconnected from larger hospitals. This gap impedes the achievement of the strategic goal of broad and effective care. Patients are inclined to visit the best hospitals in the largest cities, regardless of the severity of their illnesses; this causes overcrowding at the big hospitals and underutilization at the grassroots facilities.

Chinese doctors are living hard times. Over the last years patient-on-doctor violence has become startlingly common, mostly when treatments fail. Stabbings and mob-style attacks have risen 23% a year on average since 2002, according to the China Hospital Management Association. This situation is a huge mental burden for doctors with an average of an incident every two weeks.

Through the reform of public hospitals the State Council reiterated the need to improve the service’s quality and the competence of grassroots healthcare institutions, so that more patients can turn to these institutions for small and common illnesses, and be transferred to large hospitals in time if their conditions worsen. The other major reform’s goals are described in the image below.

These improvements will surely take time, so the significant gap in quality between grassroots facilities and large hospitals will persist for a while. However, big improvements has been achieved starting from late 1990s. The process of reform has been relevant, but the country is still far away from a well-crafted and functioning healthcare system.

While in name China has achieved universal health coverage in recent years, benefits remain low and quality and extent of care and coverage vary widely. Co-pays are often very high, certain drugs are excluded from coverage, and out of pocket expenses are insufficiently reimbursed. The out-of-pocket cost issue is the most pressing, especially in rural areas. Driven by rapidly growing healthcare costs, high out‐of‐pocket expenses comprised a major challenge for those seeking healthcare.

The State Council asked authorities to spend more effort on helping the private sector. Despite the fast growth of private investment in hospitals, the public sector still dominates around 90 per cent of all patient visits, according to a Deutsche Bank 2015 healthcare report. Private and foreign hospitals can bring leading medical technologies and advanced management, clinical practices, and service models to China; they may also partner with public hospitals to share information and expertise. Additionally, more such hospitals competing against each other for market share might help to bring down prices and improve patient satisfaction. China has made very positive steps forward to allow WFOE structures in healthcare and senior care. However, specific types of primary care, clinics and home healthcare remain within the purview of China’s Ministry of Health, with a regulatory scheme that does not know how to adequately discern between these different types of service providers. Consequently, companies who want to provide higher acuity healthcare services find themselves getting routed through a regulatory system originally designed to handle large hospital projects. These approval processes lack the sort of flexibility and streamlining that smaller footprint healthcare delivery models need.

Healthcare&Technology

China’s healthcare system, could emerge with some really innovative and disruptive ideas.

One area to be watching is within the on-line sale of prescriptions. Lots of questions remain around this, including supervision and how distribution channels between businesses and consumers will be monitored.

Despite the unsolved questions companies as Alibaba make public their intention for this to be one of the company’s strategic areas of focus over the next year.

Alibaba has made several investments in the healthcare sector, including the acquisition of CITIC 21CN, a drug data company, in order to create an app that lets users scan barcodes to verify the authenticity of their drugs; and its “Future Hospital” plan, which is an initiative to make hospitals more efficient through the use of Alipay and cloud computing platform.

An additional example is given by the Chinese Internet giant Tencent that has invested $70 million in DXY (also known as Ting Ting Group). DXY claims to be the largest online healthcare service community in China, able to link more than two millions doctors across the country.

Today, China’s largest pharmaceutical retailers are getting their own infrastructure prepared to deal with the point of sale, oversight and delivery requirements.

Despite Beijing has pinpointed that remote healthcare, Internet and technology are the drivers needed to solve its healthcare problems in a five-year roadmap in March, the barriers to enter the healthcare system are still high for the innovative actors that aims to revolutionize the system. China’s huge and fragmented public healthcare sector, despite the long process of reforms and the attempt to leave space to the private sector, is still widely populated by state-run firms who dominate the sector and don’t want change its structure.

Thus, a strong opposition to any kind of innovative change is slowing down new investments in healthcare technologies. In addition, the pace of change is delayed by technical issues related to the old IT structure that are still used in the overall healthcare system.

Another innovation in the healthcare sphere that very likely will be developed is telemedicine.

Telemedicine is getting ready to be a huge platform in China. There are great probabilities that in the near future telemedicine could provide Chinese families with the ability to get basic primary care services.

The integration between telemedicine, on-line prescription sales, on-line scheduling of follow-up diagnostic or specialty physician appointments, and electronic medical records could be a game changer for China’s healthcare system.

A last and noteworthy reflection regarding the macroeconomic effects driven by changes in the healthcare system should be done. China has one of the highest savings rates in the world – about 50% – largely because families fear catastrophic healthcare costs. Here hence, a well functioning healthcare system might be helpful to rebalance Chinese economy and to shift from an export- and investment-driven model to one supported by domestic consumption.